GTM Tool Spend by Growth Stage

Why premature tooling turns leverage into coordination cost

A founder told me something recently that perfectly captures what is quietly breaking inside modern go-to-market teams, particularly at early and mid-stage SaaS companies that are trying to look sophisticated before they are structurally ready.

They replaced five sales reps with tools.

A few months later, they hired three people whose full-time job was managing, debugging, and coordinating those tools.

Not because the tools were bad, and not because automation does not work, but because the company invested in GTM infrastructure years before it had earned the patterns, ownership boundaries, and operational discipline required to absorb that complexity without slowing itself down.

This is one of the most common GTM failures I see, and it almost always hides behind the language of best practices, modern stacks, and what serious companies are supposed to look like.

In reality, it is not a tooling problem at all.

It is a timing problem.

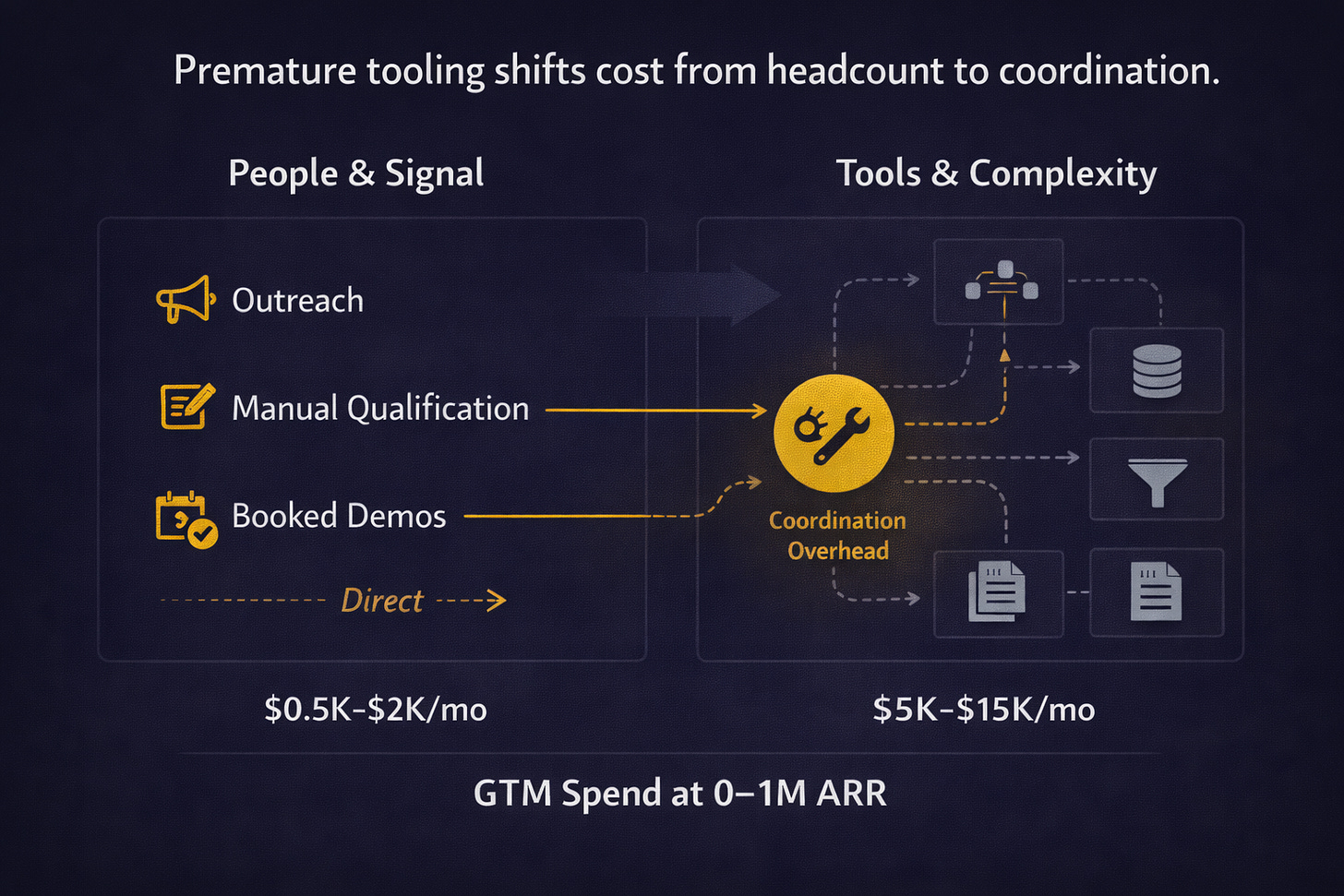

Premature tooling does not remove cost, it relocates it

GTM tooling rarely fails because of price. It fails because it fundamentally reshapes how cost shows up inside the organization.

When tools are introduced too early, cost shifts away from visible headcount and into invisible coordination overhead, where work that once lived inside a single person’s judgment is now fragmented across systems, enrichment rules, automations, dashboards, and handoffs that no one fully owns end to end.

Slack fills up with questions that should never have existed.

Automations quietly break and degrade trust in data.

Teams feel busy, instrumented, and operationally advanced, while learning velocity and execution speed quietly slow down.

This is the hidden tax of premature GTM tooling.

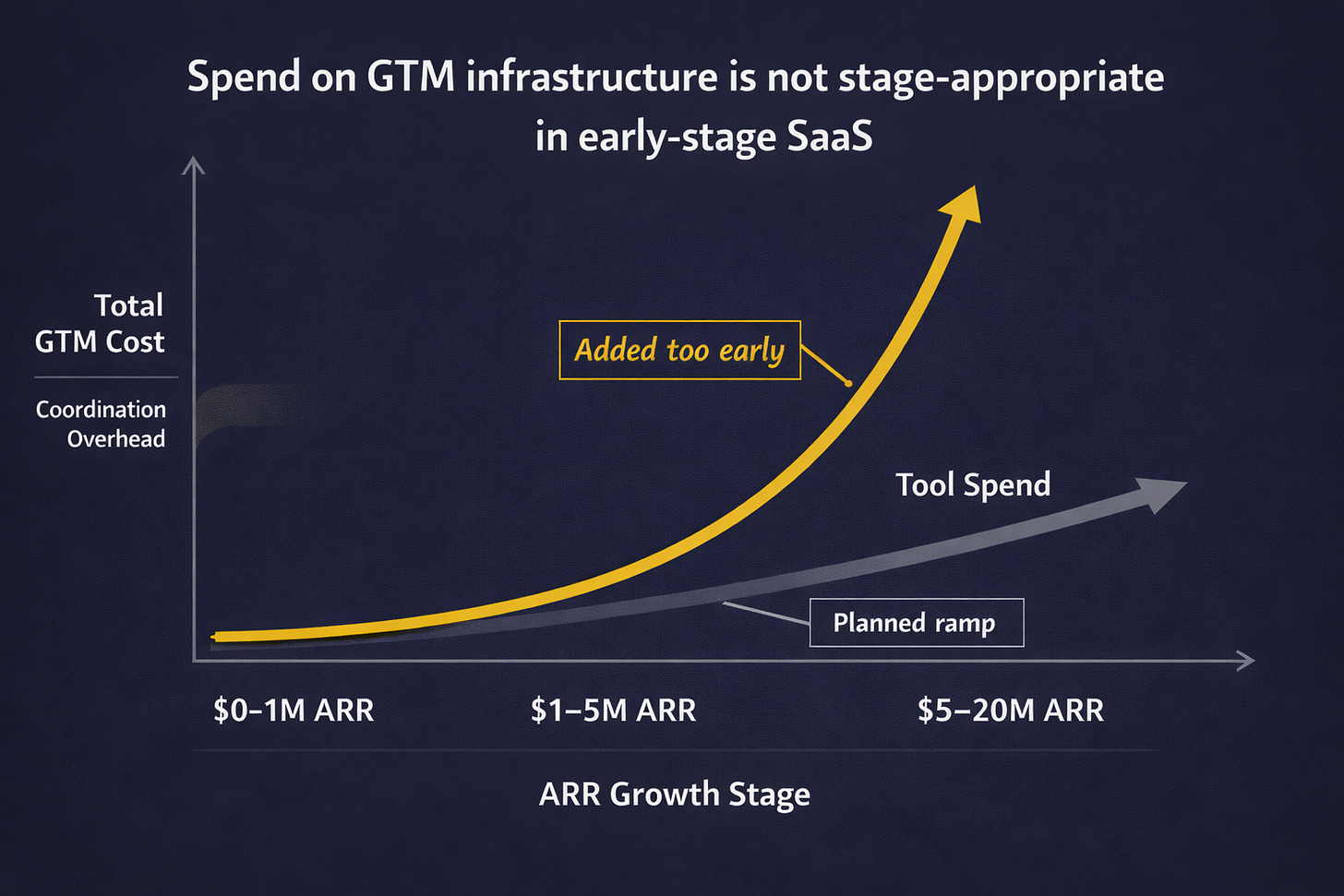

GTM tool spend is a stage decision, not a best practice

One of the most damaging habits in SaaS is copying the GTM stack of a $10M or $50M ARR company while operating at $300k or $500k ARR, under the assumption that tooling sophistication is what created their success.

At early stages, your constraint is not efficiency, scale, or coverage. It is signal. You are still learning who buys, why they buy, how they describe their pain, and what actually moves them to act. Any tool that increases distance from those signals, even if it saves time on paper, is a liability.

As companies scale, that constraint changes. Patterns stabilize. Volume introduces real friction. Only then does tooling begin to create leverage instead of noise.

GTM engineering is the discipline of aligning tool spend to that reality rather than to aspirational maturity.

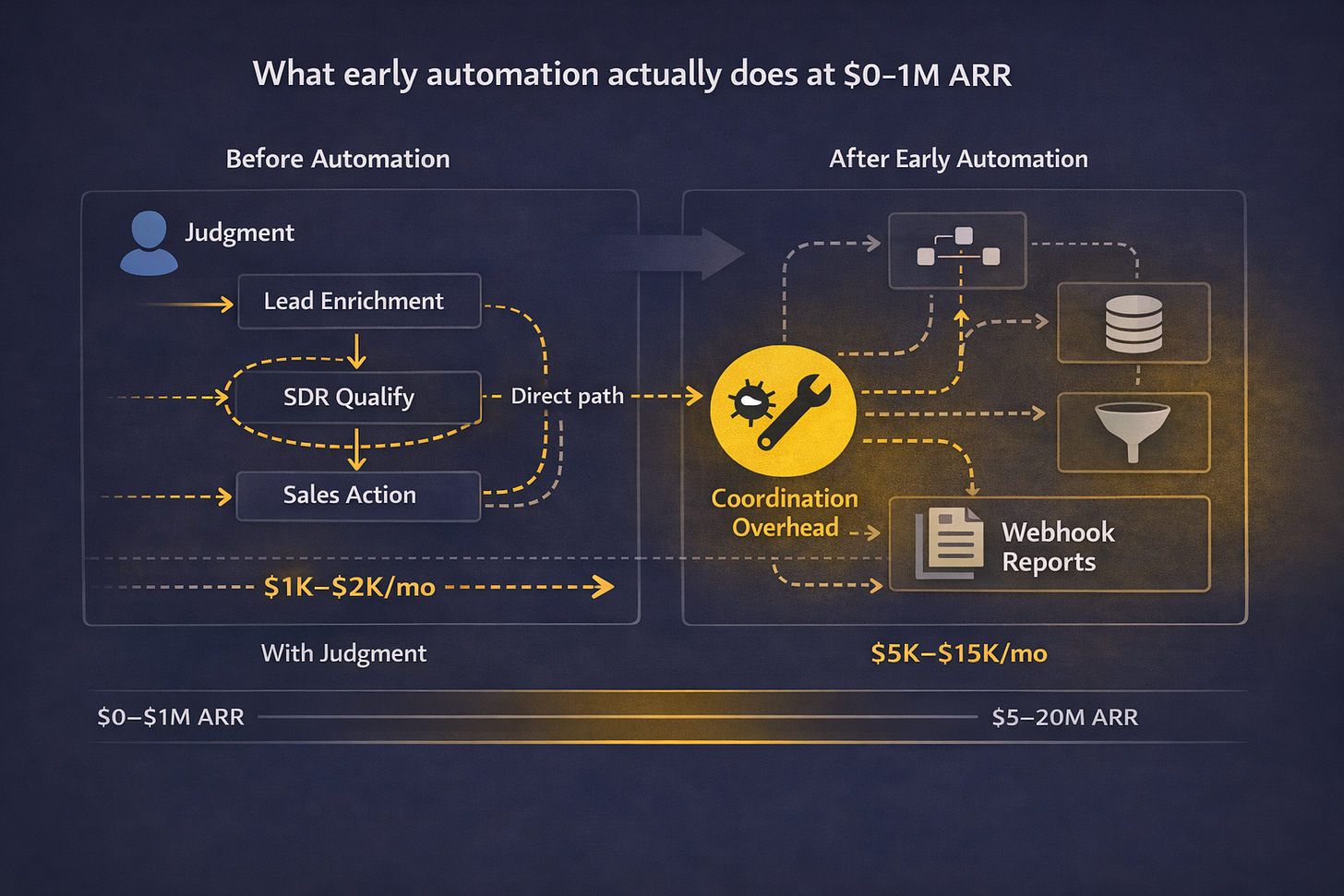

Why early automation almost always backfires

Automation is usually justified as a way to save time, but early automation rarely removes work. Instead, it redistributes it across a wider surface area that requires constant attention to maintain.

Judgment that once lived in a founder’s head is now encoded into routing logic, enrichment rules, scoring thresholds, sequences, and brittle integrations between tools. When something breaks or behaves unexpectedly, there is no single owner who can diagnose the system holistically, so debugging replaces learning.

This is how teams end up automated but slower, instrumented but confused, and staffed with operators whose primary job is keeping GTM systems alive rather than driving revenue forward.

Automation without ownership does not scale execution.

It scales coordination.

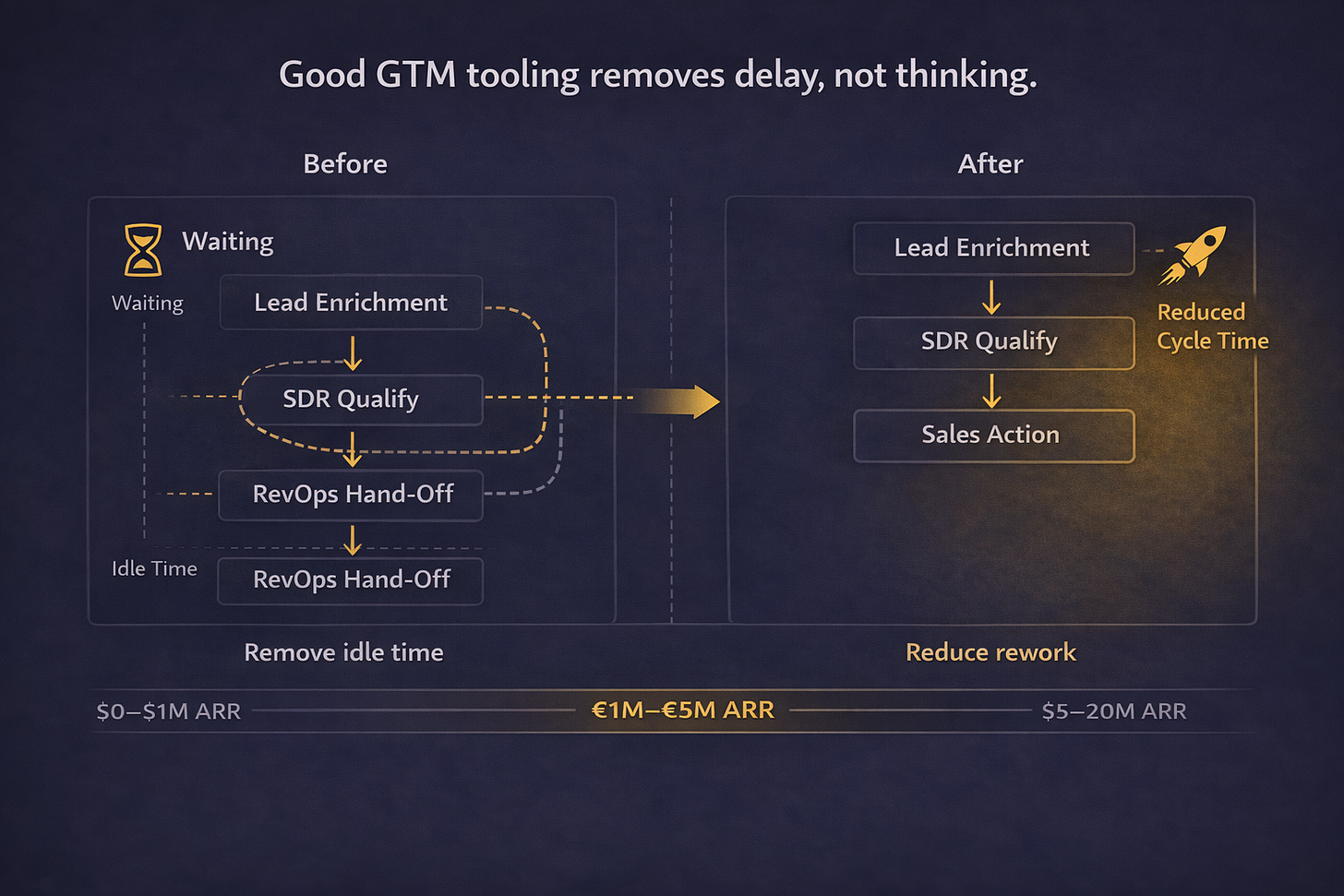

Good GTM tooling removes delay, not thinking

The highest-performing GTM systems do not move faster because people think less. They move faster because idle time disappears from the execution path.

Waiting between steps.

Repeated qualification.

Multiple handoffs for the same decision.

These are the real killers of velocity.

Good tooling collapses execution so the same owner can observe a signal and act on it immediately, without waiting for alignment, approvals, or translation across functions. Bad tooling adds layers that require meetings before anything meaningful can happen.

The difference is not sophistication.

It is flow.

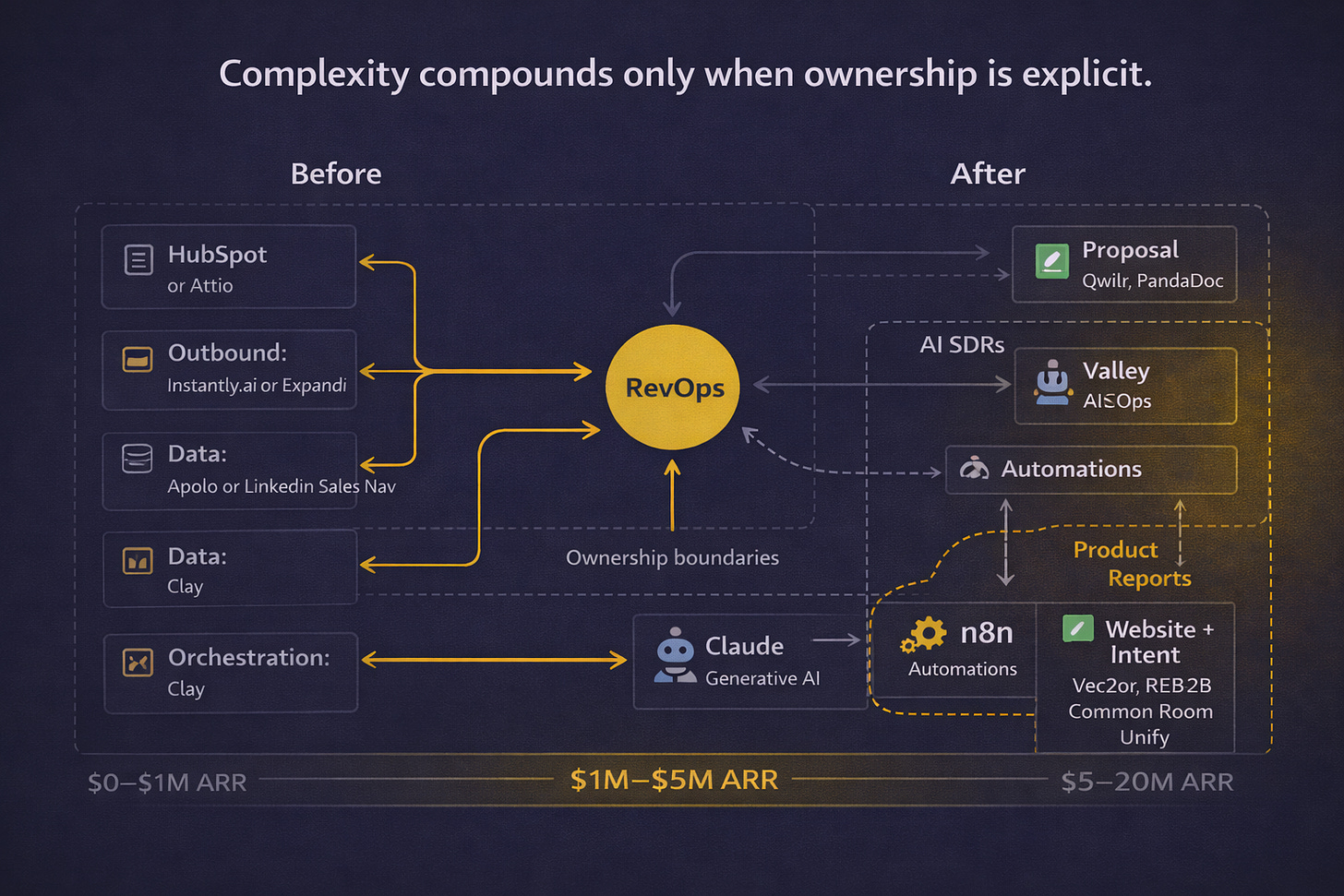

RevOps is the ownership boundary that makes complexity safe

As GTM complexity becomes unavoidable, the critical question shifts from whether to add tools to whether the organization has clear ownership over how those tools behave as a system.

RevOps earns its place when it functions as the system owner, not as a reporting layer or ticket queue, maintaining coherence as tooling increases and ensuring that every new layer reduces friction rather than introducing new failure points.

Without this ownership boundary, tools multiply faster than understanding.

With it, complexity compounds into leverage.

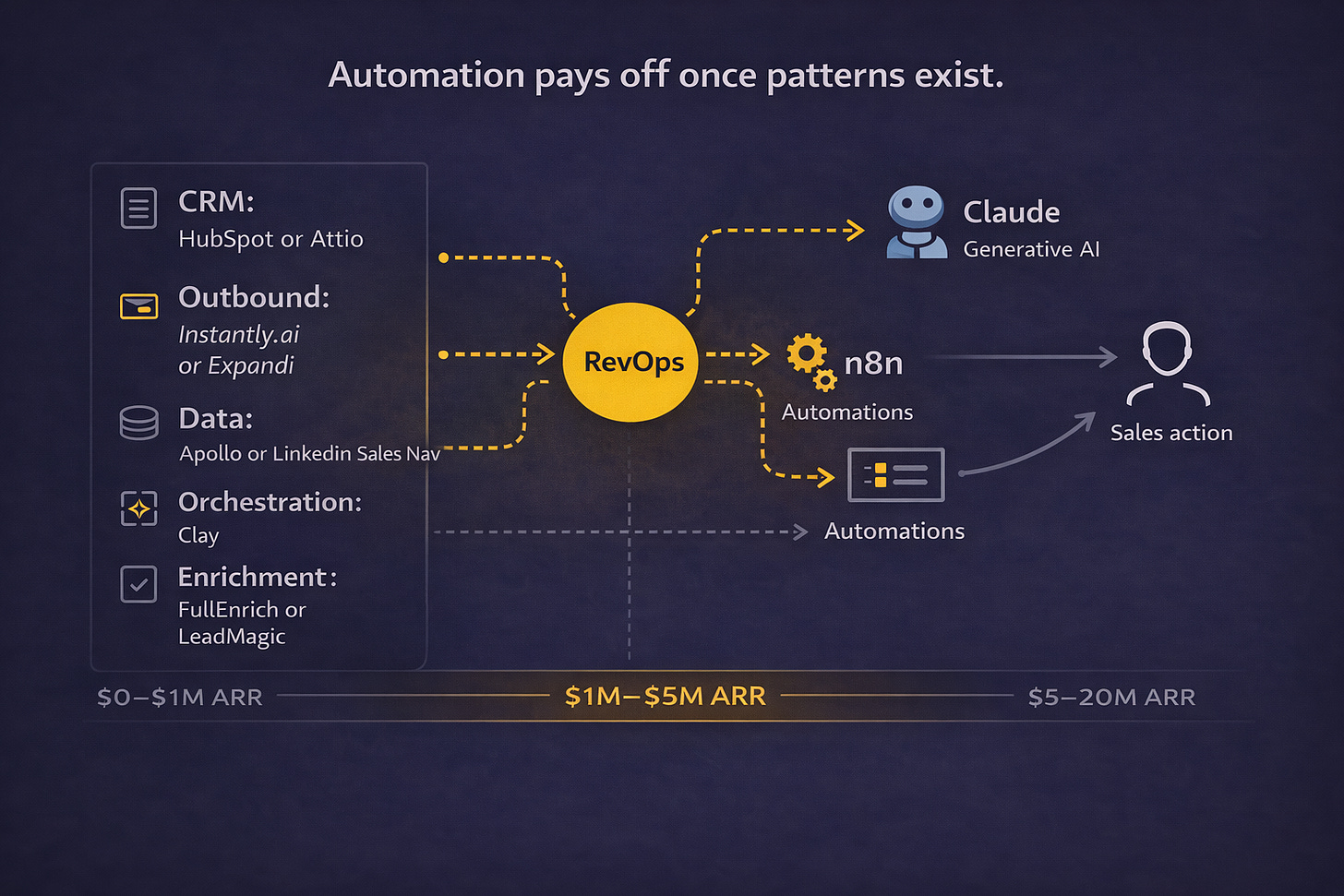

Automation only compounds once patterns exist

Automation is not inherently powerful. It is powerful only when applied to something stable.

Patterns in who converts.

Patterns in buyer behavior.

Patterns in what signals actually matter.

Before those patterns exist, automation accelerates noise. After they exist, it creates real scale.

The best teams delay automation longer than feels comfortable, then deploy it aggressively once the ground is solid. They earn the right to automate.

Early GTM optimizes for signal, not efficiency

Founder-led GTM still works at early stages because the objective is not efficiency, but learning speed.

Simple stacks, manual execution, and direct customer contact outperform sophisticated systems when clarity is still forming. Tools that reduce effort but also reduce contact with reality slow learning at the exact moment it matters most.

Efficiency comes later.

Signal comes first.

GTM engineering is capital discipline

GTM engineering is not about taste, trends, or assembling the right logos on a slide.

It is about allocating capital, attention, and complexity at the right moment in a company’s lifecycle. The best teams are not the ones with the biggest stacks or the most automation, but the ones with the fewest coordination surfaces and the tightest feedback loops.

Tools do not replace people.

They replace waiting, rework, and misalignment, but only when the organization is ready.

If your GTM stack requires more people to manage than to execute, the problem is not tooling quality.

It is timing.